Did you ever spend sleepless nights wondering what makes

a good story work? Did you ever pound your chest in a rage at not being able to

define the components of an excellent drama?

No? Well, I’ll tell you anyway.

Part

I: I Get the Nobel Peace Prize for Rediscovering the Wheel

Why not start with characters? See, it doesn’t matter if

Timmy had his parents killed, his sisters raped, his brothers maimed, his dog

stolen, and his house burned if you don’t give a rat’s ass about Timmy. You’re invested

in a story in the same degree you are invested in the characters.

It

doesn’t help if Timmy looks like a circus reject, either.

You might be thinking, “Well, that was easier than my

high school girlfriend.” Thing is there’s a second factor, and that is the plot.

See, all characters have to be tested somehow, and that’s where the plot comes

in. The harder it pushes your characters, the more engaging they’ll be. Characters

are boring if the plot doesn’t put them to the wringer, and the plot is

irrelevant if it doesn’t affect (and is affected by) interesting characters.

Part

II: The Cold War Was Actually Pretty Hot

Now that I’m done pretending I made a major discovery, I

want to reintroduce the idea of using history as a basis for epic fantasy. See,

fantasy thrives on big canvases and life-or-death stake. It makes sense to

exploit history to build plots that’ll put characters through the most

skin-thickening crucibles imaginable.

Allow me to use an example from recent history to show

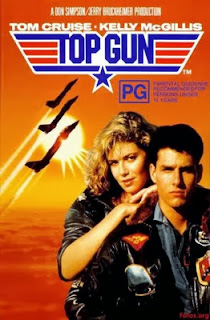

what I mean: The Cold War. You know, the war which taught us that Tom Cruise’s

career would be the most schizophrenic thing since James Joyce’s entire

literary canon.

Good

Bad

Remember what Faulkner said about the only kind of

writing that matters is the one about the human heart in conflict with itself?

(And I did read that speech long before I knew who George R.R. Martin was,

thank you very much.) The same applies to civilizations. Characters in a story

are riveting when they act in ways that don’t conform to the conceptions they

have of themselves.

If the USA and the USSR were the main characters of the

Cold War, how did they come into conflict with their own ideologies?

Funny you should ask, because I happen to have the

answer. Let’s go step by step.

The

United States:

1) First one is actually a team work. In 1951, the nationalist Prime Minister of Iran, Mohammed Mossadegh, directed the Iranian Parliament to vote for the nationalization of the oil industry, challenging the authority of the Shah (or king, if you will). The pickle is that he also stepped on the toes of the British. See, at the time, most of the Iranian oil industry was in the hands of the British, who pocketed the bulk of the revenues. The British felt they had a right to do that. After all, they had discovered and exploited the oil with technology and talents that they brought to Iran.

1) First one is actually a team work. In 1951, the nationalist Prime Minister of Iran, Mohammed Mossadegh, directed the Iranian Parliament to vote for the nationalization of the oil industry, challenging the authority of the Shah (or king, if you will). The pickle is that he also stepped on the toes of the British. See, at the time, most of the Iranian oil industry was in the hands of the British, who pocketed the bulk of the revenues. The British felt they had a right to do that. After all, they had discovered and exploited the oil with technology and talents that they brought to Iran.

Winston Churchill, the old-school

imperialist who once again assumed the role of Britain’s Prime Minister in 1951,

convinced the United States that Mossadegh was moving Iran toward communism.

The CIA wasted no time. The agency created a situation of instability by

bribing army officials, criminals, and politicians, and by staging protests and

riots in Tehran, the Iranian capital. The chaos took its toll. In 1953,

Mossadegh was arrested by the army and the Shah was restored to the throne.

For its efforts, the United States got a

share of Iran’s oil and continued to sell weapons to the ever more hated Shah

and his SAVAK, the Iranian secret police.

So next time you see Iranians burning

the American flag you might understand why they’re so pissed off.

2) This

one is closer to home. In 1951, another nationalist, this time one Jacobo

Arbenz, became the democratically elected president of Guatemala. This in a

time when a small handful of landowners owned about 70 percent of the land.

Like in Iran, foreign interests (in this case the US) owned most of the

economy, so the actual wealth ended up going abroad. The United Fruit Company

alone used little more than 15 percent of the land they owned, leaving the rest

uncultivated.

Arbenz nationalized unused land in

defense of Guatemala’s national sovereignty, trying to curb the power of

foreign conglomerates. To the CIA, this smacked of communism, so they supported

rebellious and opportunistic elements in the Guatemalan army that carried out a

successful coup against Arbenz.

Guatemala went to hell in a hand basket

after that. Brutal military regimes tried to keep things quiet with an iron

fist. The more infamous of these enforcers was General Efrain Rios Mott. On his

orders, the army murdered 70,000 of their own people, primarily Mayan peasants,

and burned down thousands of villages in a move that wasn’t far removed from

genocide.

But

hey, at least he was a Born-Again Christian.

3) The 1973 military coup in Chile is probably the most infamous example of US interventionism in Latin America. Chile was the first country to democratically elect a Marxist president in 1970. Salvador Allende proceeded to nationalize the nitrate and copper mines, extend land reform, and raise the workers’ wages.

The CIA supported the Chilean military in deposing

Allende, thus helping institute one of the bloodiest military dictatorships in

South America. Augusto Pinochet, the general who took over the government, was

the driving force behind Operation Condor, an underground alliance of military

strongmen in Chile, Argentina, Bolivia, Brazil, Paraguay, and Uruguay in which

members pooled resources and intelligence to track down and terminate opponents

in Latin America, the United States, and Europe.

Courtesy of Brazilian artist Latuff2

It was in 1973 that

President Nixon’s national security advisor, Henry Kissinger, proved that the

Nobel Peace Prize is an even bigger joke than professional wrestling.

Kissinger, the recipient of one such award, had given his tacit approval to the

Chilean coup by stating “I don’t see why we have to let a country go Marxist

just because its people are irresponsible.” He also knew about Operation Condor

and said nothing against it, thus enabling the Dirty War in Argentina and

scores of “disappearances” throughout Latin America.

His partner-in-crime, Nixon, is also infamous for stating

that the plan against Salvador Allende should make the Chilean economy scream.

The

screaming bit wouldn’t stop with the economy, though.

The Soviet Union and China:

1) You

would think revolutionaries stick together, but if you truly believe that then

you haven’t been paying much attention to history. In 1949, the Chinese Civil

War finally came to an end. The Communists under Mao Zedong finally defeated

the Nationalist government and took the reins of China. Was the Soviet Union

(specifically Stalin) happy to have a fellow communist nation right next door?

Not in the slightest.

Stalin had signed a treaty at the end of

World War II recognizing the Nationalist Chiang Kai-Shek as the legitimate ruler

of China, never mind that the Chinese communists had been fighting Chiang for years

now. Stalin even advised the communists at some point not to fight the

Nationalists, because they didn’t stand a chance of winning. It wouldn’t be out

of place to imagine Stalin might have been much happier with a weakened

Nationalist government in his back yard than with the revitalized, gung-ho

Communist government he got instead.

You

could almost feel the love.

2) One

of the myths of the Cold War that the United States believed all the way to the

end was that any and all communist insurgencies in the world originated from

the Soviet Union. And as much as the Soviets would’ve loved to say that was the

case, it wasn’t. The myth led to the belief that all communist governments

worked together to further the communist cause across the globe. The US went on

believing this myth even when evidence piled up that this couldn’t be further from

the truth.

Take Vietnam. Who you think

proposed the idea that Vietnam be divided into north and south in the first

place? The Western powers? Well, it seems it was actually Zhou Enlai’s

idea--the foreign minister of the People’s Republic of China. The Soviets found

the idea attractive, too. The West jumped at the chance to divide Vietnam rather

than let the whole country go communist. Zhou Enlai let it be known that he

would have been fine with a permanent division of Vietnam, letting ancient

ethnic divisions trump the ideal of communist fraternity.

3) When Stalin died and Nikita Khrushchev came to power, the Soviet Union was a formidable fortress around which the United States was building spheres of influences. Khrushchev was not going to let the USSR be encroached upon by their enemies. In order to stay in the fight, the Soviets would have to become global players, as well--even at the expense of their ideology.

The first client state they adopted was

Egypt, ruled by Gamal Abdel Nasser. So what if Nasser was an anti-Communist,

had shut down the Egyptian Communist Party, and didn’t balk at jailing

communists? The Soviets needed a foothold outside Eastern Europe.

Man wasn't shy about smiling, either.

Things get even murkier when Indonesia comes into the

picture. Still hoping to expand their sphere of influence, the Soviets began selling

weapons to the Sukarno government. The Indonesian Communist Party, the third

most powerful communist party in the world after its Russian and Chinese

counterparts, voiced some complaints, but they died down when the fledgling

Sukarno was forced to rely on the Indonesian communists to keep his government

afloat.

The problem came when Sukarno was

deposed by a rival, Suharto. Using the well-armed Indonesian army, Suharto

launched a bloody purge that eliminated half a million of suspected and real

communists alike, destroying the Indonesian Communist Party and those “guilty

by association” in one fell swoop.

Part III: I Ramble a Little Longer

See, as people we have expectations of how the world should be and how our actions contribute to or diminish that idealized vision. The same goes for nations, only on a much larger scale and with many more players involved.

See, as people we have expectations of how the world should be and how our actions contribute to or diminish that idealized vision. The same goes for nations, only on a much larger scale and with many more players involved.

There’s nothing shocking about what the United States and the Soviet Union did during the Cold War, not if you’re familiar with history, at least. Whenever a culture is strong enough to influence others, it will exercise that power. Individuals and nations will be caught in the crossfire; that’s the way it’s always been.

It’s not history’s job to pass judgment, though. It exposes facts as best as it can and tries to fit everything into a bigger picture. It helps illustrate what it means to be human by giving an account of cultural interactions.

The questions that rise from these studies can be the launching pad for wonderful fiction, however. They stem from the core conflicts that have underpinned humanity since the advent of civilization. They’re as compelling and relatable now as they were two thousand years ago, and they deserve our attention.

Epic Fantasy is the perfect platform to explore these questions at leisure, because the genre buffer resets our biases to zero and allows us to concentrate on the historical questions themselves, not on what these questions mean to us as Americans, Russians, Chinese, Guatemalans, or whatever. It’s about what they mean to us as human beings.

Stay tuned for more.

No comments:

Post a Comment